The Hidden Mechanics of Planned Obsolescence and Its Impact

Written on

Chapter 1: A Glimpse into Planned Obsolescence

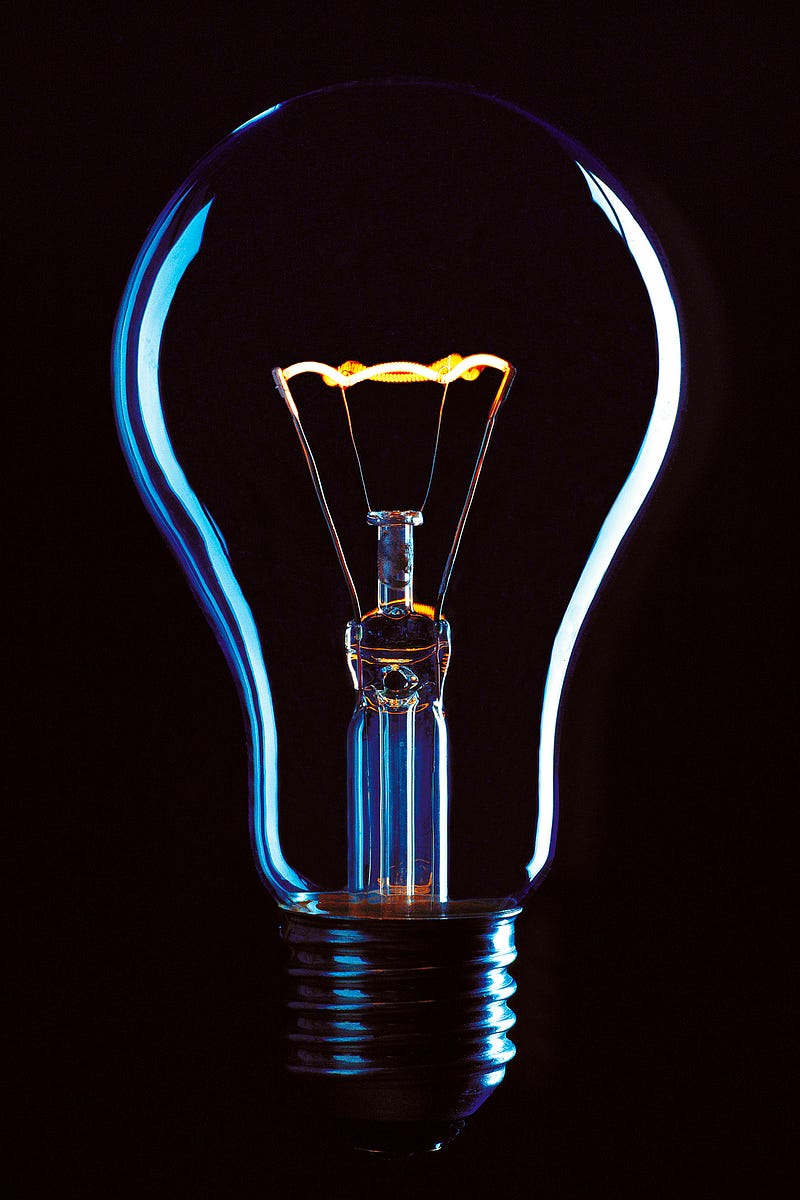

In the annals of industrial history, a significant narrative unfolds that exposes the less savory side of capitalism. It starts with a simple light bulb and expands into a web of conspiracies affecting everything from vehicles to mobile devices. This exploration delves into the intersection of history, technological advancements, and corporate avarice, shedding light on why we frequently find ourselves purchasing replacements for items that could have endured much longer.

The Centennial Light Bulb: A Testament to Longevity

At the Livermore Fire Station in California resides a remarkable artifact known as the Centennial Light Bulb. This bulb, which has been illuminating since 1901, challenges contemporary assumptions about the durability of light bulbs. Handcrafted in the early 20th century, it has shone continuously for over a million hours—a feat that seems almost legendary in an age where light bulbs are engineered for far shorter lifespans.

The Formation of the Phoebus Cartel

The narrative of why today’s light bulbs lack the longevity of the Centennial Light Bulb traces back to 1924 in Geneva, Switzerland. Here, key representatives from top light bulb manufacturers, including Phillips, International General Electric, and OSRAM, established the Phoebus Cartel. Named after the Greek deity of light, this cartel was not a benign collaboration aimed at technological progress. Rather, it was a calculated scheme to restrict the lifespan of light bulbs to a mere 1,000 hours.

Engineering for Short Lifespans

Prior to the cartel’s inception, the lifespan of light bulbs had been gradually increasing. By the 1920s, many bulbs lasted as long as 2,500 hours. However, the Phoebus Cartel perceived long-lasting bulbs as a threat to their profitability. They conspired to shorten product lifespans, ensuring that consumers would need to buy replacements more often. Engineers, once focused on extending product life, were now tasked with figuring out how to curtail it.

The Decline of Durability

The cartel's strategies proved successful. By 1934, the average light bulb lifespan had plummeted to just over 1,200 hours. Members of the cartel scrutinized each other through rigorous testing and imposed penalties on any manufacturer whose bulbs surpassed the agreed-upon limits. This artificial curtailment of product longevity not only boosted sales but also allowed these companies to sustain higher profit margins by maintaining stable prices despite reduced production costs.

Planned Obsolescence: An Ongoing Strategy

The concept of planned obsolescence did not conclude with the Phoebus Cartel; it evolved and permeated various sectors. In 2003, Casey Neistat's viral video drew attention to Apple’s use of planned obsolescence, showcasing how an 18-month-old iPod’s battery failure led to exorbitant repair costs that made purchasing a new device more appealing. Apple faced legal challenges over throttling older iPhones’ performance, a move ostensibly made to protect batteries, but which also nudged consumers toward newer models.

The Right to Repair Movement

Opposition to planned obsolescence is gaining momentum. In the European Union and over 25 U.S. states, proposed laws aim to solidify the right to repair. These regulations would mandate manufacturers to supply parts and information necessary for consumers to repair their products, potentially extending their lifespan and minimizing waste.

The Fashion of Obsolescence

The automotive sector, spearheaded by General Motors in the early 20th century, also adopted planned obsolescence. GM’s strategy of introducing annual model updates and new colors was designed to render older models obsolete, encouraging customers to purchase the latest versions. This practice, known as dynamic obsolescence, was intended to sustain high sales by making consumers feel their current possessions were always out of date.

Technological Advancements vs. Consumerism

Interestingly, not all forms of obsolescence are negative. Technological advancements have greatly enhanced the efficiency and longevity of products like light bulbs. The shift from incandescent to LED technology, for instance, has significantly reduced energy use and extended lifespan. Modern LED bulbs can last up to 50 times longer than their incandescent counterparts.

Conclusion: A Beacon of Hope?

While the practices of the Phoebus Cartel and similar strategies have cast a long shadow over consumer goods, a glimmer of hope remains. The push for the right to repair, along with the rise of more durable technologies, hints at a future where consumers may not need to replace their devices as frequently. However, as long as fashion trends and market dynamics influence consumer behavior, planned obsolescence will likely continue to be a complex challenge.

Understanding the evolution of planned obsolescence and its ramifications on our everyday lives is vital. It empowers consumers to make educated choices and advocate for more sustainable practices. The next time you replace a light bulb, a phone, or a vehicle, reflect on the story of the Centennial Light Bulb and ponder how different our world could be if products were designed for longevity.

Chapter 2: The Videos on Planned Obsolescence

This video discusses the implications of planned obsolescence and its effects on consumer products, urging viewers to reconsider their buying habits.

A detailed exploration of why many products fail to last, examining the strategies employed by companies to encourage frequent replacements.

References: