# Weather Insights: The Invisible Force Shaping Our World

Written on

Chapter 1: Understanding Weather Dynamics

Today, I intended to create some videos while testing one of the latest units. After flying a few 3D-printed RC planes to warm up, the weather took a turn for the worse, and I found myself flying in the rain during my maiden flight. It was a thrilling experience, although it meant I couldn’t conduct any paraglider tests. Our testing window was limited to 9–10 AM.

Since 2010, I have poured considerable passion and effort into grasping the intricate processes that govern our planet. I often contemplate the boundaries of these processes and where they might lie. My journey began in 2008, when I started sailing by repairing boats damaged by hurricanes. This led to a series of milestones:

- 2010: Refocused on the Carbon Cycle Project at the International Space University.

- 2012: Took up paragliding.

- 2015: Launched Anticip8, a weather analytics startup at Singularity University.

- 2017: Became the Express 37' National Champion in sailing.

- 2018–2020: Worked with Monark on weather analytics and global sensing at Airbus and Acubed Innovation Center.

- 2020: Featured in BBC’s Super Powered Eagles and PBS NOVA’s Eagle Power while tandem paragliding with Lloyd Buck.

For me, comprehending weather is crucial for the safe operation of flying vehicles and is fundamental to achieving widespread adoption of autonomous technologies. It's essential to assess all potential risks and opportunities for enhancing performance.

I have a deep appreciation for sailing and paragliding; both activities rely solely on sunlight and wind. Other vehicles can adopt this mindset to ensure safe takeoff and landing.

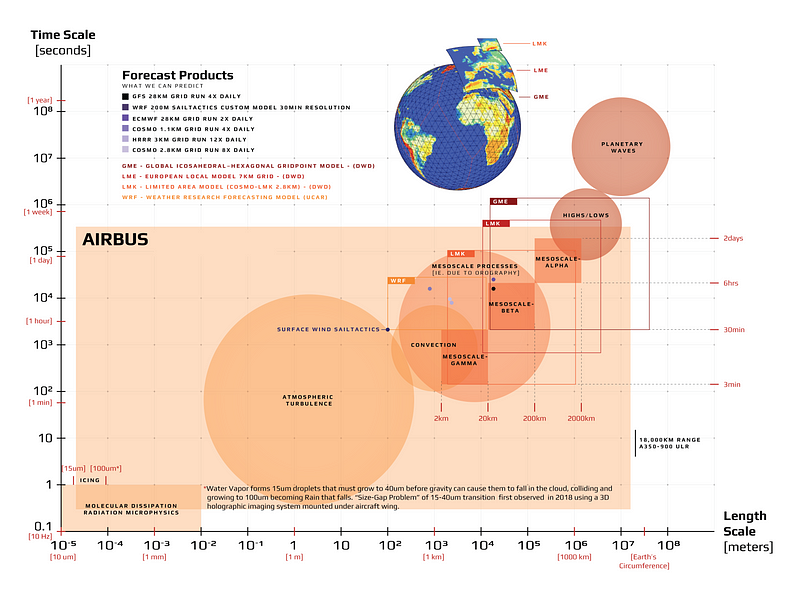

The discourse surrounding weather and climate can be challenging due to their varying scales of time and space. It might sound unusual, but how can I discuss the tiny insects dancing in the early morning sun around my plants alongside the wind-driven sea spray that influences hurricane formation?

This complexity also contributes to the difficulties in fully understanding the physics involved in weather and Earth process modeling. To achieve accurate forecasts, parameters must be established ahead of time. Where is the boundary for these predictions?

A profound quote from Gerard K. O’Neill's "2081: A Hopeful View of the Human Future" resonates with me:

> Von Neumann envisioned that by the 1980s, computers would predict weather with great accuracy. Yet, our forecasting capabilities remain largely unchanged from decades ago. The Earth's atmosphere is vast, encompassing a billion cubic miles, influenced by sunlight, cloud cover, oceanic and terrestrial heat exchanges, and solar particles. Perfect predictions would require not just infinitely fast computers but also an extensive network of sensors monitoring temperature, pressure, humidity, wind, and other variables at every point in the atmosphere. In reality, data is collected just twice a day, and often from remote locations, leaving large regions like oceans and deserts underrepresented. Surprisingly, the quality of weather predictions can be more affected by governmental budget decisions regarding sampling than by technological advancements in computing.

Since 1980, we've witnessed significant strides in both sensing technology and forecasting skills, but we haven't reached the limits of what's achievable. Many advanced UAV projects and high-altitude platforms focus primarily on design and customer capabilities. The closure of Loon highlights the challenges faced; understanding how to navigate and maintain stable flight is critical. This is closely linked to weather conditions. Initiatives like Perlan 2.0 and HAPS platforms are exploring new phenomena at high altitudes that remain largely unknown. Sail drones are filling the observational gaps over oceans, but there’s still much ground to cover. Each incremental improvement offers cascading benefits for life on Earth.

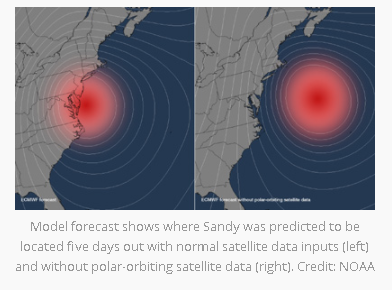

Consider the implications of understanding drought cycles as our planet is dynamic. The more we grasp how our observations influence the near and distant future, the better we can manage resources. For instance, Planet IQ's study on Hurricane Sandy revealed that if a few polar orbiting satellites had been absent, forecasts would have suggested Sandy would veer out to sea—an inaccurate prediction based on the actual events.

To illustrate, GNSS-RO measurements play a vital role in data assimilation to enhance weather forecasts. Currently, NOAA aims for 20,000 measurements daily, but they’re achieving only about 2,000–5,000 due to various satellite constellations and partnerships. Recent trial funding programs have escalated from $100k to an expected $22–24 million annually.

Weather balloons also incur substantial costs—nearly $1 million each day to release 2,800 balloons globally. Aircraft-based sensing programs, like AMDAR, are also in play, yet we need significantly more humidity measurements worldwide.

It's critical to explore how we can expand sensing without generating waste, recover costly sensing systems, or develop biodegradable, affordable options. The Joint Center for Satellite Data Assimilation (JCSDA) is dedicated to integrating diverse datasets to improve forecasts, not limited to just space-based sensors.

I could elaborate extensively on this topic. I enjoy flying in thermals, fleeting pockets of warm air released by trees or animals—it's a wild experience. Currently, automated systems lack the capability to engage in such playful interactions, but when they do, it will seem like magic—merely a result of Earth’s physics.

Chapter 2: The Science Behind Wind and Weather

In the video "Where Does Wind Come From? | Richard Hammond's Wild Weather | Earth Stories," Richard Hammond delves into the origins of wind, explaining its significance in weather patterns and climate.

The second video, "How Does Weather Actually Work? | Richard Hammond's Wild Weather Compilation | Earth Stories," provides insights into the fundamental mechanisms that drive weather systems, enhancing our understanding of this complex field.